Feb. 14, 2022

•5 min read

I had just taken my kids to see a movie at Mayfair Mall. Sonic 2 if you must know. We had left the theater and were making our way to Barnes and Noble when I saw an exhibit at the end of the hall. It was for Negro League Baseball. Maybe you’ve seen it too. And sitting at the table in front of a stack of books and signed balls, surrounded by jerseys and memorabilia was Dennis Biddle. I walked up, curious. He smiled and introduced himself as the youngest living player from the Negro Leagues. He’s 87. He looks great and is sharp as a tack. I was blown away. How is a player from the Negro League at a card table at Mayfair Mall? I shook his hand and made a donation for his book, Secrets of the Negro Baseball League.

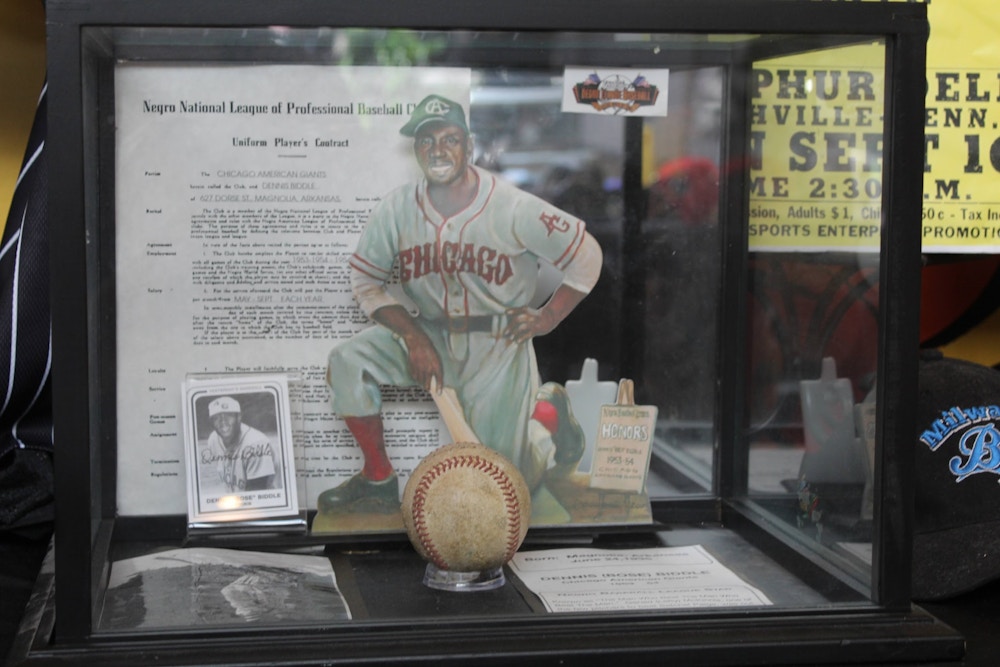

I went home and devoured it. It was a terrific read, and nothing like I thought it would be. Yes, he talks about how he made his debut in 1953 when he was 17 years old pitching for the Chicago American Giants. He wrote about the hardships and the bus rides and how the Negro Leagues would make money on the side by playing against the white players until they kept beating them so badly it started to look bad for baseball. It talked about how when Jackie Robinson was picked up by the Brooklyn Dodgers a lot of people assumed the Negro Leagues ended, but instead the majors used the Negro Leagues as a minor league system, without the pay or the credibility, until it just kind of withered away with no official end.

But that was just the first quarter, if that. So much of the book is about Biddle’s fight for legitimacy to get his fellow players from the Negro Leagues—the players that Major League Baseball (MLB) and documentaries and baseball fans love to fawn over—organized so they could receive official recognition and finally get some of the money that everyone had been making off of them, for themselves.

Biddle has been helping people all his life. He was born in a small segregated town in Arkansas. He likes to say, “I come from a town of 9,999. When I was born I made it 10,000.” He went to an all-Black school. His mom was a missionary, his dad was a deacon. Five brothers, one sister. At a young age he remembers helping people at the church with paperwork. “My mom and dad instilled in us Love. Not only for one another but for everybody.”

He was a naturally talented player and was picked up by the Chicago Giants. It’s a great story, but you’ll have to buy the book for that one. At the end of the 1954 season he got a letter saying the Chicago Cubs had bought his contract and he had the opportunity to try out as a non-roster player. In the spring of 1955 he flew to Arizona for training camp and on the first day of practice he broke his leg on a slide into third. After six months of rehab he felt like he was better than ever. But the Cubs passed.

So he went back to what he knew best. Helping people. He went to college at the University of Wisconsin and became a social worker for the state. He become a job developer, working with companies that did on-the-job training and helped hundreds and hundreds of people get hired.

Years later he worked for the Ethan Allen School for Boys, a reform school in Delafield. They placed the kids that didn’t want to go to school, that mom and dad couldn’t handle, with him. He was like a father to them. They finally had someone they could talk to and trust. A skill that would soon serve him well when working with his fellow players who were burned badly by those using them to make a buck.

Patrice, Biddle’s wife, said men still recognize him at Mayfair and come running up saying, “This man saved my life, this man turned my life around!” She showed me a picture of a man who insisted on giving Biddle a big hug and a kiss and took a photo together.

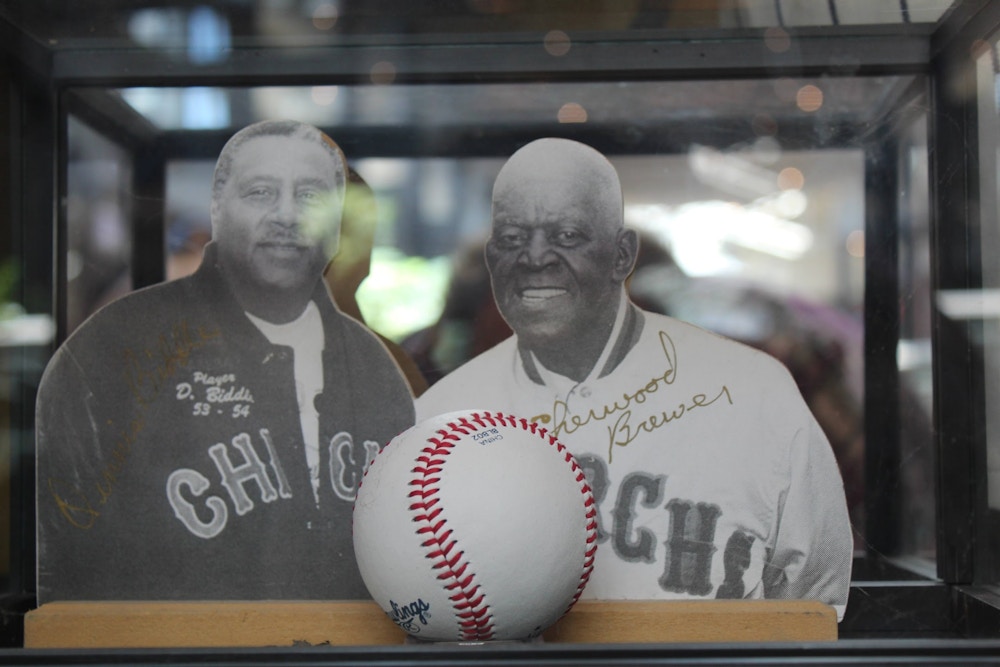

After a stress-induced heart scare, he retired. But he didn’t rest. Immediately, he met the man who he would share maybe the most important chapter of his life with, another former Negro League player, Sherwood Brewer.

In 1995 the Negro Leagues celebrated their 75-year reunion at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. They did interviews, signed autographs, and caught up. On the last day Buck O’Neil—a former Negro Leagues player and manager of the Kansas City Monarchs—spoke to the remaining players. The former players had questions about MLB possibly covering their health insurance, giving out pensions, and who was eligible. Also, they wanted to know who was receiving all the money from the museum. Because it seemed like only O’Neil and a few select players he handpicked were profiting. Everyone else was left out.

I told Biddle, O’Neil kinda comes off as the bad guy in his book. He set me straight. “Buck’s not a bad guy. Guys didn’t make much money back then. And Buck was in a position to make some money. He got the money that he would never would have had, and the credibility that he never would have gotten.”

Biddle definitely had compassion for O’Neil, but that still wasn’t how he did things. According to Biddle, “If you played at all, you should get something.” And as he was leaving the hotel he said to his wife, “I need to do something.” Sherwood Brewer overheard him and asked, “What did you just say?” Biddle gave him his name and number and the next thing he knew, he was picking him up from the bus station in Milwaukee. Their goal was to help every person who played in the Negro Leagues for any amount of time the compensation and recognition they deserved.

Biddle told me he could have easily just gone on the circuit with Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe, the catcher who caught his first game, making millions signing autographs and doing appearances. But Biddle thought about all the men who were falling through the cracks. All the men the historians missed. He thought about his time in social work, “The Lord was preparing me to do what I do now.”

Spoiler alert: This story does not have a perfect happy ending. Over the years Biddle has had some wins and some losses. With the help of Bud Selig and his son-in-law Laurel Prieb, vice president of corporate affairs for the Milwaukee Brewers, some of the former players did get pensions. All while people tried to destroy his credibility, even going so far as to say he never really played in the Negro Leagues. But thanks to Biddle they are now organized and recognized through an official group that Biddle and Sherwood Brewer started, Yesterday's Negro League Baseball Players Foundation (YNLBP). The money they make from autograph sessions, Negro Leagues nights at ballparks, and the money he makes from his corner of Mayfair Mall—it all gets split up between the living players.

Biddle tells me a story that encapsulates his struggle with happy endings particularly well. In 1996, the Milwaukee Brewers set up a Negro Leagues night for former players to sign autographs and be recognized.

It was such a big hit that Biddle put together a pro-bono Wall of Fame recognizing Negro Leagues players for County Stadium. A huge success, albeit one Biddle had to pay for himself. But when County Stadium closed and Miller Park opened, the Brewers organization decided to nix YNLBP Wall of Fame and replace it with a Wall of Honor that only recognizes two living Negro Leagues players a year.

Biddle was signing autographs when a woman told him she had put in a bid for his Wall of Fame on the internet. He was shocked and heartbroken, but he refused to be discouraged. Biddle immediately called his attorney and had the bidding stopped. The deacon of Holy Redeemer Church of God in Christ requested the Wall of Fame and that is where it currently resides.

While we spoke at the mall a couple of men came up to ask Biddle about a marker they saw at Borchert Field near Rose Park. He knew exactly what they were talking about and dove right into how that park hosted the Negro Leagues’ Milwaukee Bears in 1923. I tell him I can’t believe how quick he is for 87 years old. He tells me, “The Lord preserved me for this.”

There’s still much work to be done, but the Lord has Dennis and Patrice Biddle working on it. Together they’ve created Bridging Gaps to Greatness, “a non-profit youth initiative of YNLBP to improve fundamental skills, education, and self-esteem for young athletes as a proven recipe for lifelong success on and off the field.”

There’s also the advocacy component for the surviving players. Patrice reminds me, “People think they’re all gone. And they’re not.” Along with Linda Paige, Satchel Paige’s daughter they created the Save the Legacy campaign which passed a resolution in Detroit for May 20th to be known as Negro Leaguers Recognition Day. They are hoping more people will sign their petition at Change.org and more cities will adopt the day of recognition. As Patrice says, “It’s not just Jackie Robinson.”

I asked Patrice why she feels it’s so important to get this story out, why it’s so important to pass on.

“Our children don’t know the history, and I think there's a lack there because they don't realize the value in not just that history but various aspects of our history that brings pride. I think that they lose a sense of identity that they need to have … Not just focus on the lack and the slavery. We need to hear other aspects of it, the greatness. Why did they become so great? In the face of the adversity that they faced. How did they persevere? … What made them legendary even to this day. So that they can pick up some of those characteristics and understand the importance of holding on to that, because that sense of pride that they have, that they didn’t buckle, they didn’t fold. They didn’t argue, they didn’t fight, they persevered and became the best at their craft … Become the best at your craft. Be so great at what you do people will see your greatness without you having to fight for it … That’s the secret that our children need to know.”

And then she flipped it around and reminded me why it’s so important to a white guy like me, too. “It’s so that other cultures can understand what it took and how they persevered and why it happened … and not feel in any way that bringing up the history is gonna cause some type of hate or ill feelings toward the history of your ancestors that you need to feel shame but so that we can create an opportunity to make a resolve and to change the dynamics of how we interact as a people.”

On July 22 the Milwaukee Brewers will have their annual Negro Leagues Tribute Night. Dennis Biddle will be there, and he’s already looking forward to it. So am I. Dennis has lived so many lifetimes in his 87 years and told me enough stories to double this article, easily. Which means maybe you should swing by and meet him for yourself. He’s at Mayfair Mall every Thursday, Friday, and Saturday spreading the good word and taking donations to help out his fellow players.

I asked Biddle, with all that he’s done and all the people he’s helped, what he thinks his legacy will be. He tells me, “I just keep doing my job, doing the best that I can.”

I tell Patrice, “He’s incredible.” She smiles, “He wears greatness well.”

More Articles by Mike Betette

Jan. 25, 2023

•6 min read

Nov. 28, 2022

•9 min read

Aug. 17, 2022

•9 min read

About the author

Mike is an improviser and writer who has performed with The Second City, Jimmy Kimmel Live!, and was a writer/director for Epic Rap Battles of History. He’s currently a senior copywriter at an ad agency in Milwaukee and loves to be outside.