On the top floor of an old mansion on 8th Street in Milwaukee, Barry Poltermann is hanging window treatments for his new office.

“I don’t think I have the right hardware,” Barry says, frustrated. Like any artist facing a challenge, he plunges forward, grabbing a drill.

Barry splits time between here and Los Angeles, where he conducts much of his business nowadays. After he moved I remember talking to him about how the world, at least for him, is different now.

“You tell people you edited American Movie, and their face lights up,” he says. “People come up to me and say, hey, that movie is the reason I wanted to be a filmmaker!”

American Movie, the 1999 film that won the Grand Jury Prize for Documentary at the Sundance Film Festival, directed by Barry’s longtime friend and collaborator Chris Smith, has become iconic. It’s a cult fascination for filmmakers and makes frequent appearances on “greatest documentaries of all time” lists. But, in 1999 a film like American Movie really had no place to go.

In 1999, there was no Amazon. No Hulu. No Netflix. Can you even imagine it?

Still, there was a small and fervent cottage industry that surrounded the film. Among filmmakers, it was always held in high regard. Many say they saw the film for the first time in a film class. The film’s protagonist, Mark Borchardt, became kind of a cult hero. Barry reveled in that moment; but didn’t sleep on it. There is always a story to tell somewhere.

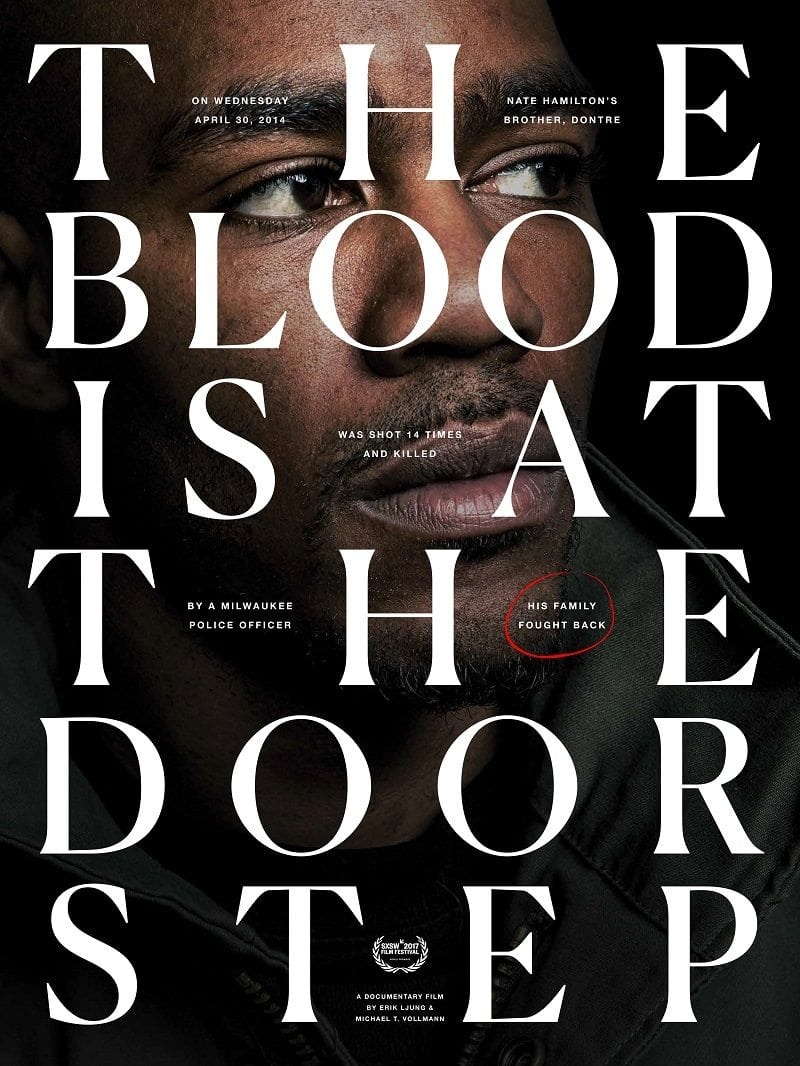

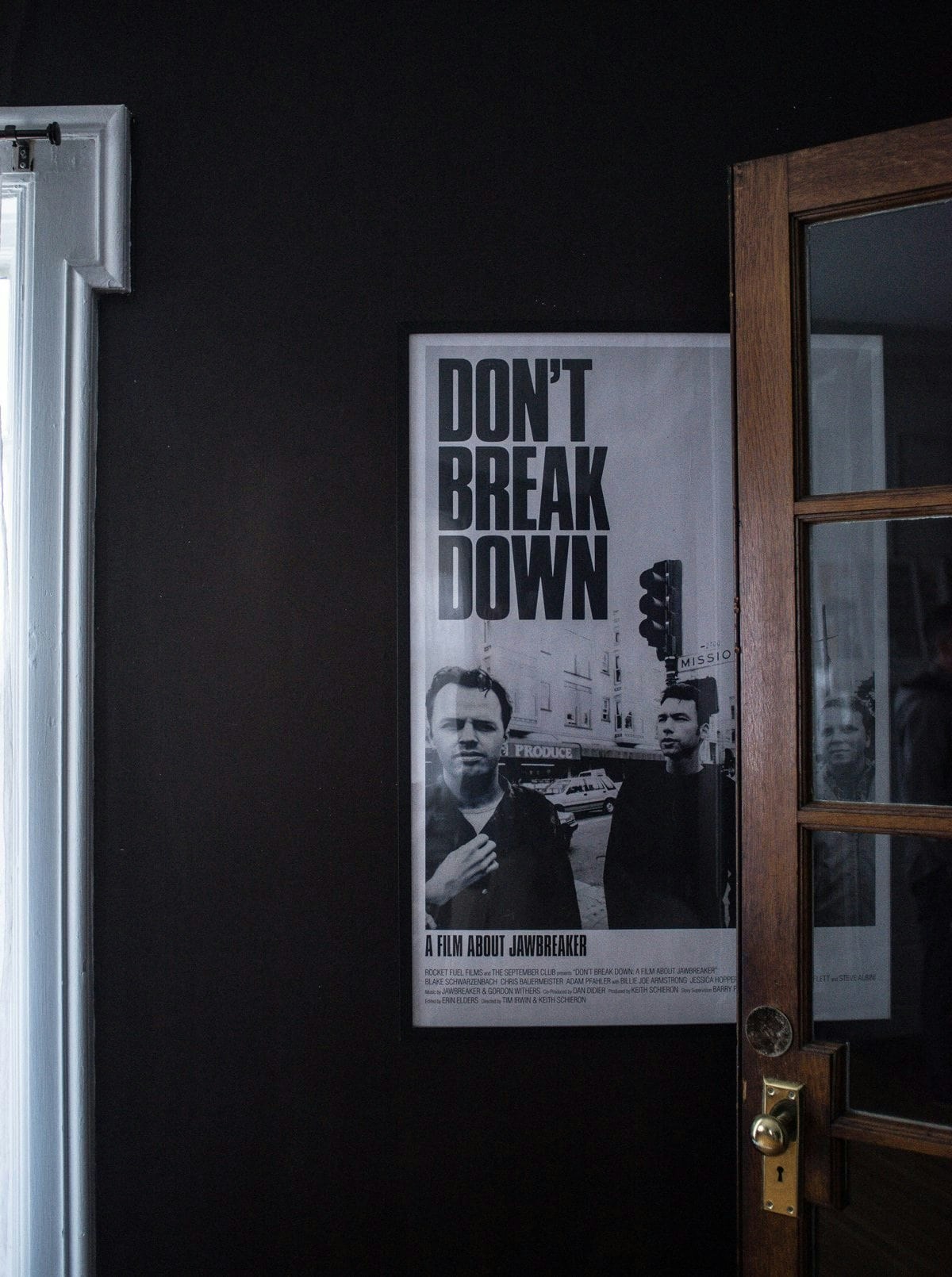

Those stories are evident as you walk through the front doors of the old mansion-now film office. You see what has happened since American Movie – film posters of the work Barry has co-directed, edited, supervised, produced and or financed adorn the walls. Life of Reilly. Rock the Bells. Psychopath. Collapse. Don’t Break Down: A Film About Jawbreaker. The Blood is At The Doorstep. Raiders! The Story of the Greatest Fan Film Ever Made.

Barry’s documentary company, The September Club is named for the month in which entries are generally due for the big film festivals. It’s a constant reminder of the goal he and his team are working towards. He also is co-owner of About Face Media, the branded entertainment part of the business.

…how can I make the story elements dynamic where people don’t just watch it as documentary, but as a movie?

With the democratization of camera equipment, there are a lot of people calling themselves filmmakers these days. But good film editors are more rare. As a documentary editor Barry’s job is to slog through hours and hours of footage, working in lockstep with the director to build a narrative. “I’ve cut narratives in a month or two, but a doc takes a year – it’s a lot more complicated,” Barry says.

Barry is a student of storytelling. He speaks of the Truman Capote novel “In Cold Blood” as ground zero for what he calls the “non-fiction narrative.” In the documentary world, Barry cites 1994’s Hoop Dreams as the movie that changed everything. In fact, while editing American Movie, Hoop Dreams was a key influence. Barry explains, “There was a moment when we were cutting and were conscious of a non-fiction narrative influenced by (TV shows) Cops and The Real World – and making it into something as compelling as the TV show – how can I make the story elements dynamic where people don’t just watch it as documentary, but as a movie?”

Before Hoop Dreams, documentaries were simpler, and were not crafted in the way narrative films were crafted. Barry’s guide has always been the pillars of filmmaking, 3 acts, well rounded characters, and maybe the most important element of all: Conflict.

The editor/director partnership in documentary film is as essential a relationship as art’s relationship to craft. Barry’s working partnership with Chris Smith is one of those relationships. And, while Barry and Chris have certainly taken separate paths, that creative relationship has never wavered. It was sometime in 2016 when Barry’s phone rang, and there was Chris’s familiar voice.

He had some remarkable footage he wanted Barry to go through. 100 hours of it.

Ironically, the same year American Movie came out, another film, Man on the Moon was released. Over 15 years later, the historic trajectories of these two films would converge.

For the uninitiated, Man on the Moon is the Milos Forman directed biopic about the life of comedian Andy Kaufman. It was met with great acclaim and many of the accolades were directed at Jim Carrey, whose remarkable portrayal of Andy Kaufman was lauded by critics and earned him a best actor nomination at the Academy Awards (he won the Golden Globe).

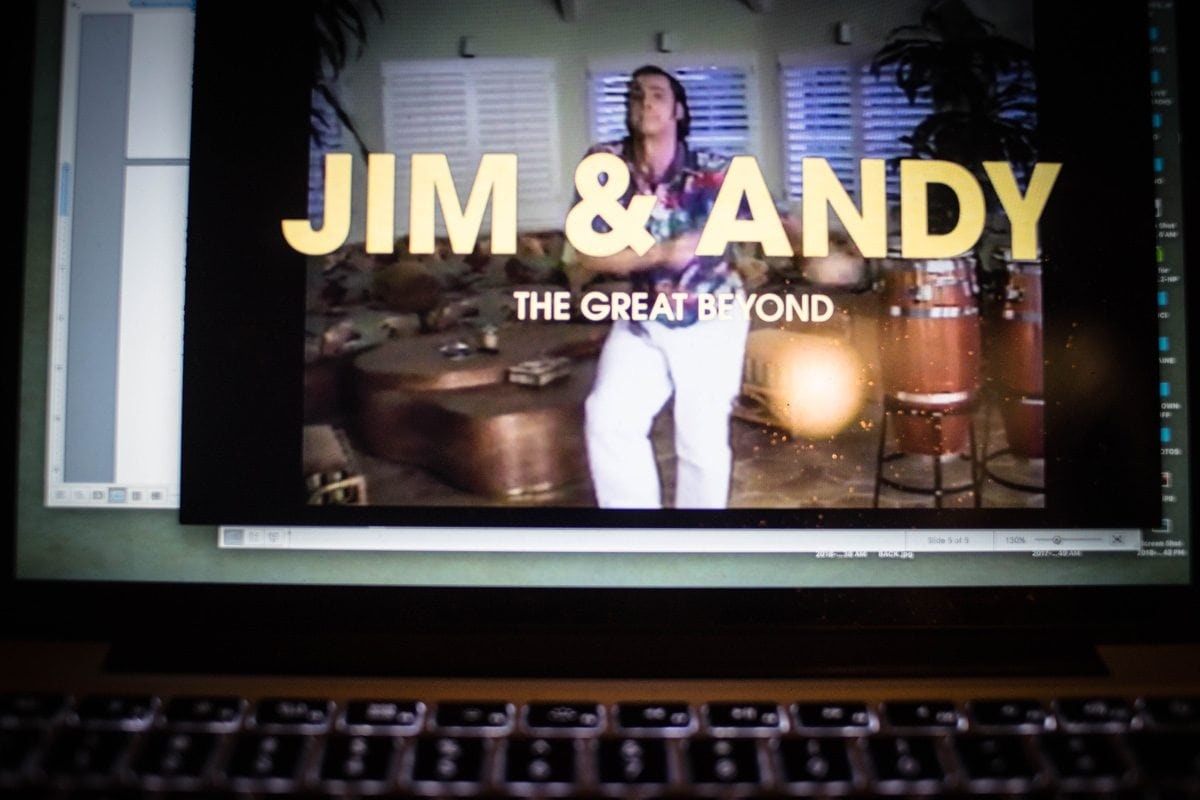

There’s a key moment in the (ridiculously long-titled) documentary, “Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond – Featuring a Very Special Contractually Obligated Mention of Tony Clifton,” directed by Chris Smith and edited by Barry. Jim had just won the part of Andy Kaufman, and speaks of the moment he walked out on the beach and saw a group of dolphins diving through the ocean. He took it as a sign from Andy – and decided that he would channel the spirit of Kaufman. Jim, for all practical purposes, vowed to BECOME Andy Kaufman.

And Jim did become Andy. During the movie shoot, Jim acted as Andy on and off set, and Andy’s girlfriend Lynne Margulies filmed behind the scenes footage of Jim being Andy. Jim had the footage but Paramount didn’t want it to see the light of day. Jim explains, “They didn’t want people to think I’m an asshole.”

The footage is a treasure trove, a window into the psyche of an actor in the midst of one of the deepest, most profound identity crises you’ll ever see. Jim doesn’t want to be Jim He wants to be Andy. And at least to my eye, he never breaks character.

The story of how the footage got in Barry’s hands goes like this: The accomplished film director, Spike Jonze, had become Creative Director for Viceland. He knew of the footage, being a friend of Jim (Spike wanted to direct Ace Ventura 2, but Jim didn’t go for it. Jim admits the mistake and regrets not choosing him). Spike calls Chris because he wanted to turn the footage into an hour show for Vice’s Guide To Film. Spike asks Chris if he wants to be part of the project. And then Chris calls Barry.

“They didn’t want people to think I’m an asshole.”

From the beginning the expectation was that the footage would be edited into a one-hour show and played for laughs. But after the footage was cut down from 100 hours to a more manageable four by Barry and his editorial staff, Chris and Barry recognized the potential. Their instincts upon seeing the 4-hour cut was that there was much more in here than just a TV show.

Barry thinks back to that time: “My guess is that Spike was hoping we would do something like we did – this movie is how he thinks – it’s a Spike Jonze film as much as anything – I would imagine he hired Chris because he thought he would do something interesting with this.”

They conducted two interviews with Jim, and the bulk of the film, according to Barry was pulled from the first interview. During the interview, Jim opens up and explores his personal demons, his family life, and his mental mindset at the time of filming Man on the Moon. He’s a man at war with himself. But here’s the thing: At the time of the interview Jim is still under the assumption that he’s being interviewed for a show about the making of Man on the Moon, not a 2-hour deep dive into his state of mind. It’s likely why he’s so relaxed and so frank.

Barry recalls, “When they saw the first assemble (the 4-hour cut from the footage) I remember the producer calling and saying this is the most interesting footage I’ve watched – I couldn’t turn it off. There’s a lot you could do with this. Still, they (Vice) were thinking behind the scenes. But with documentary you don’t know what it is – you’re just thinking it could be this or that. So much is defined by the questions the director asks and the responses that they get.”

“We were hired to do a four cut with the ultimate goal to make a TV show,” Barry says. “It was going to be this funny behind the scenes thing; they thought they would interview Danny Devito and Milos Forman – but at that point we (Chris and I) were thinking this could be different — Vice could say no, but you hope you make something more interesting than that, especially since you have Spike Jonze behind it, going to bat for you to make it more interesting.”

And make it more interesting is exactly what they did. When the Jim interview, combined with the behind the scenes footage was finally fully realized into a feature film, Vice got on board. And Jim was astonished at the results.

The next thing you know, Barry was on a plane for Venice, Italy.

The first time Barry Poltermann met Jim Carrey was at the Venice Film Festival.

Director Chris Smith introduced the two of them and Jim reached out to shake Barry’s hand. It was one of those “time stands still” moments for Barry, an accomplished and established editor. Jim looked at Barry and said:

“Thank you so much … you captured how I feel about the world and how I am looking at things now and where I’m at and the journey I’ve gone through – you’ve captured it so well and it was so unexpected. I was at my house sitting there, I got this DVD in the mail – I popped it in … and it was just a gift.”

It was an incredibly satisfying moment for Barry; the film would go from Venice, to Toronto, then ultimately to Netflix. The irony of it all is that it’s likely that more people have seen Jim & Andy than have seen American Movie.

“But you're always terrified right?”

Barry’s Venice experience was unlike any other he had in film. “At Venice the audience loved it. But you’re always terrified right? Everyone saw the movie and they liked it, but you get 1000 people in a room, you wonder, what if it lays an egg because it’s not as funny as people think it’s going to be? People go in thinking it’s going to be a laugh riot – but it’s more complex, more challenging.”

Funny how a challenging film like Jim & Andy can actually be fun to watch. A multi-layered story about conflicting identities and personal crises and filmmaking is equal parts fascinating and complex. There are times when you’re not sure what is real and what isn’t real. It’s kind of like Orson Welles classic documentary F For Fake, which Barry looked to for inspiration during the Jim & Andy editing process.

It’s been a long road, a road that he’s still on, working towards the next project, “If we don’t have projects in the pipeline by September, we’ve failed,” he says.

As he moves away from a film about a crisis of identity, one thing is still true: Barry will always most certainly be Barry.