Chuck Dwyer, “The Dry Points” and the Greatest Milwaukee Art Show You’ve Never Seen

Share on:

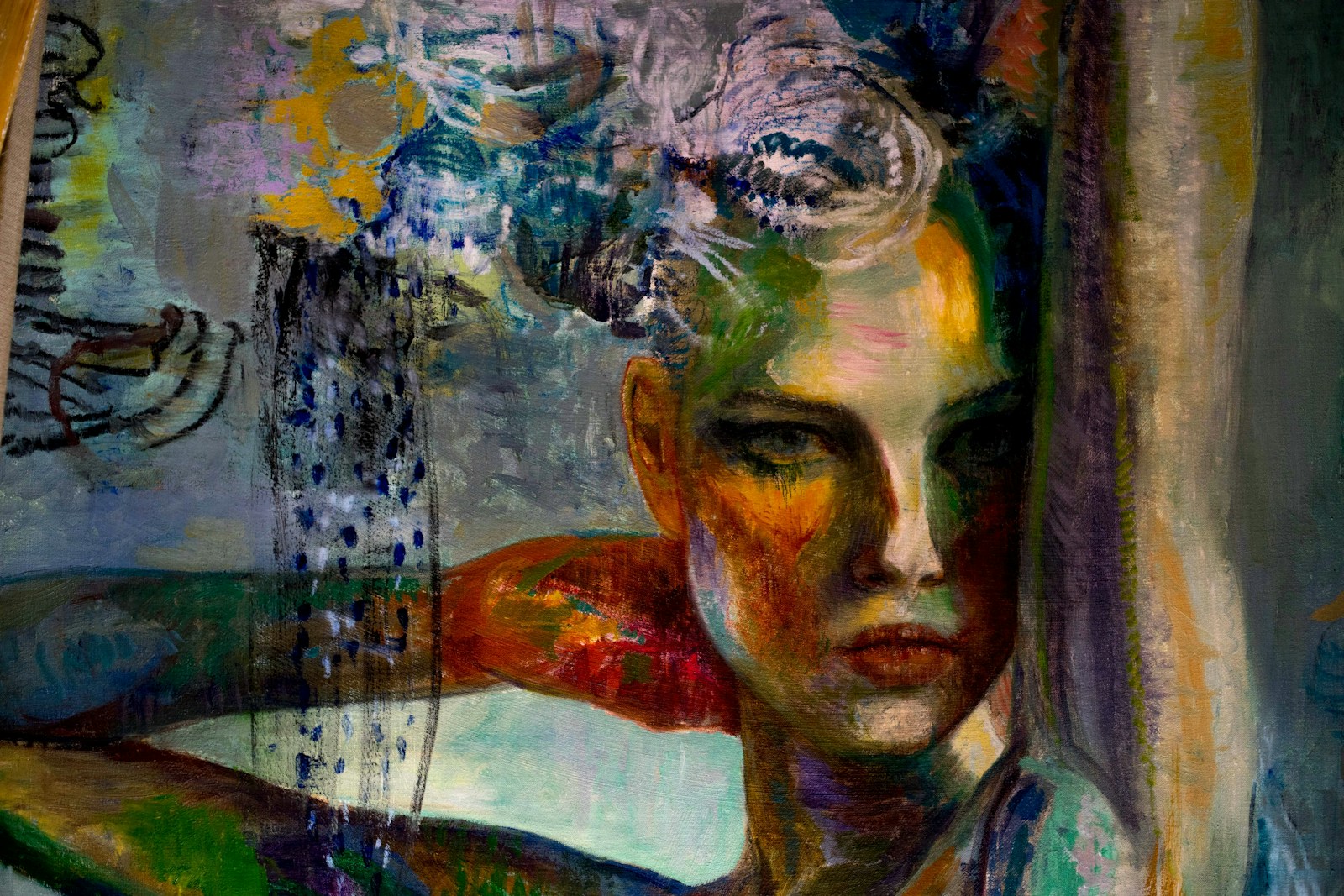

Chuck Dwyer pulls what looks like a massive folder made of thin repurposed wood out from behind a stack of canvases against a wall in his art studio. The studio is well kept, art materials neatly organized over two or three tables and a painting—a stunning hybrid figure drawing/painting work in progress—is leaning against the back wall.

Duct tape holds the makeshift folder together and Brett Waterhouse, curator of the Grove Gallery here in Milwaukee, kneels down to start cutting the duct tape to open the folder. I can see the excitement in his eyes at the prospect of viewing an impressive collection of original artwork he hasn’t seen in a few years.

I’m surrounded by artists, Chuck’s tight circle of friends who are here on a Sunday to do what might shock some for a group of creatives: watch the Packers game. It’s damn refreshing; these guys are far from stuffy, pretentious artistic types.

To my left is Adam Beadel, fantastic letterpress typographer, to my right is Stanley Ryan Jones, artist and accomplished photographer (his portraits of the 80s punk rock scene are highly acclaimed); Chuck, a brilliant and accomplished artist in his own right (more on that later) is hovering, waiting for the last piece of duct tape to get cut.

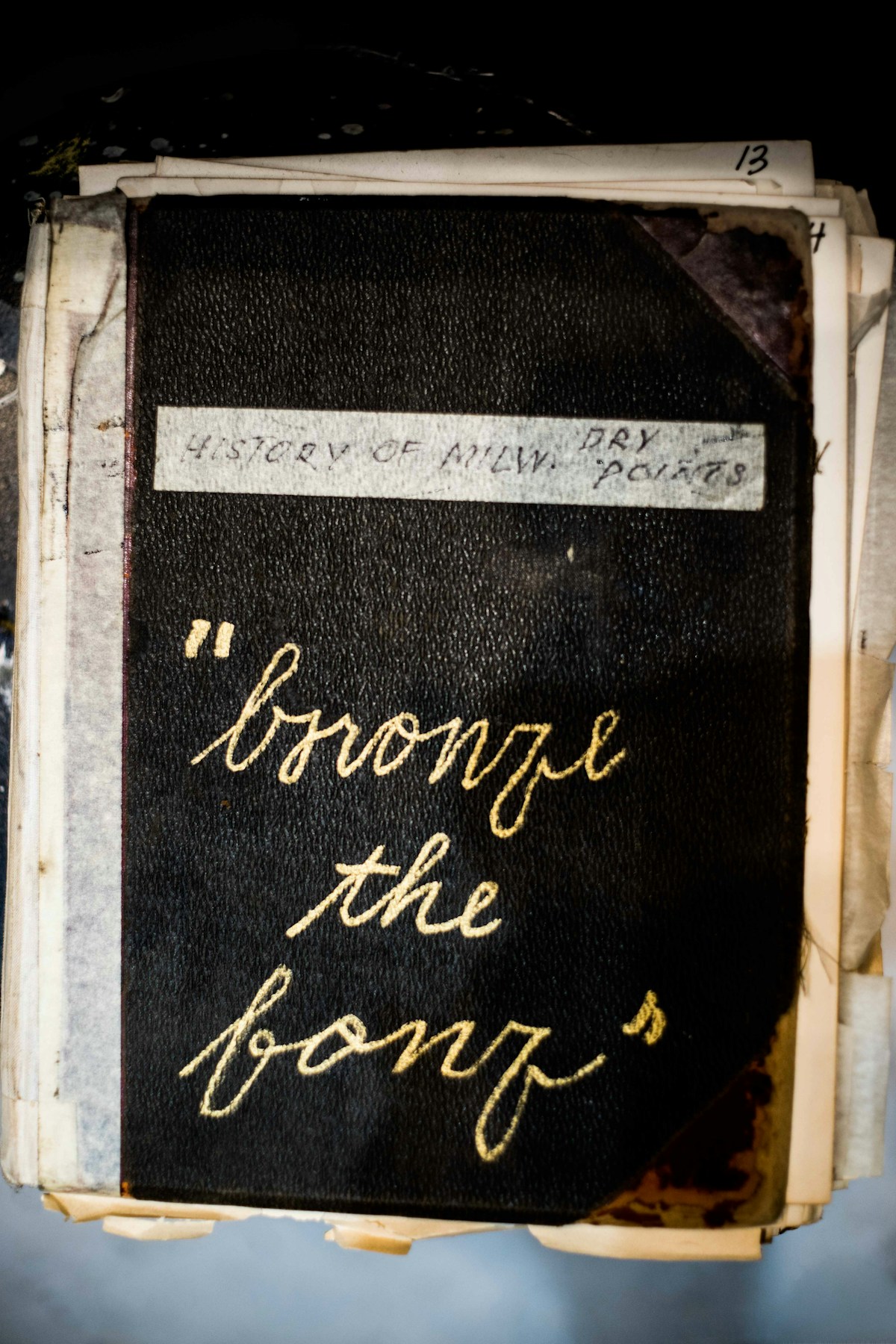

Brett flips the top piece of wood over and underneath it is a stack of about 80 pieces, each 30-by-40 inches. They are high-resolution enlargements of steel engraved portraits from The History of Milwaukee. The enlarged portraits came from a book that Chuck found at an estate sale; the book is a thick leather tome from the late 1800s. Chuck wrote “Bronze the Fonz” in gold marker on the cover to make it his own.

This book became the impetus for one of the greatest Milwaukee art shows few have ever—and most have never—seen.

Brett starts going through the pieces, portraits of historic Milwaukeeans embellished by a mix of art disciplines applied to the portraits, a bizarre and incredible mashup using just about every method and material imaginable that almost becomes its own style. It’s pop art and typography and impressionism and everything in between.

Each one is more startling than the next in its originality and inventiveness.

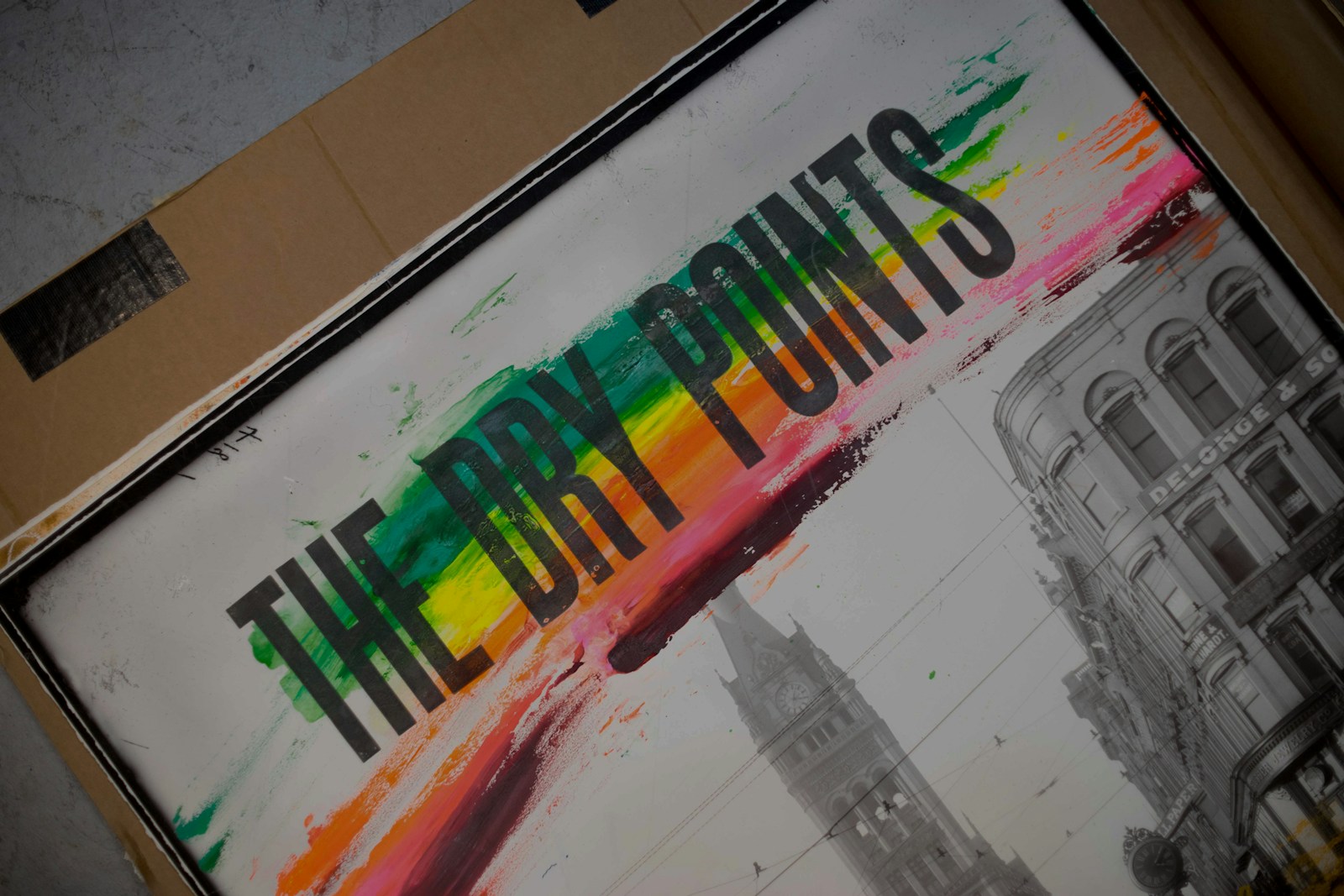

What I was witnessing was the work of a group that called themselves “The Dry Points”, a “band” of artists who got together once a week to create these pieces. An underground art scene, criminally underexposed, brilliant in every way. Their “maxim” as they call it on The Dry Points website is this:

“The ultimate goals are rowdy self-expression and collaborative experimentation. There are no mistakes.”

No mistakes. Yeah. I was here for a reason. But this would not have happened if it weren’t for a meeting I had with Chuck a week earlier, over coffee.

I did not know Chuck Dwyer, and only wanted to meet him because of a recommendation that came from the brilliant artist Nina Bednarski. I respect Nina’s opinion immensely, so I did a little digging, and discovered Chuck on Instagram as “Tainted Loft”. I would learn later that the name, also the moniker for his Bayview abode, is a riff on the 80s new wave hit “Tainted Love.” I’m sure being a middle aged single guy has nothing to do with it.

His Instagram feed is never populated with more than five photos at any one time, and the glimpses I got of his work, striking figures that are a hybrid of drawing and painting were engrossing, beautiful, and frankly, strangely mysterious in all the best ways possible.

I need to know this guy, I said to myself, so after a bit of correspondence I found myself sitting outside Anodyne Coffee on Bruce St. where I willingly tell Chuck that I know nearly nothing about him.

He laughed between puffs on a cigarette, and said, “Perfect.”

Over the next hour or so I found Chuck to be affable, introspective, multi-dimensional, and endearing. He spent his formative years working for a restoration company, where he honed his skills using a myriad of art materials (hence the hybrid nature of his work). “If I had to write an artists statement,” he tells me, “it wouldn’t be about why I’m making it, but about how I’m making it.”

Chuck’s work was showing at a gallery in Illinois in the early 90s when someone from Playboy Magazine strolled in, saw his incredible work and asked Chuck if he wanted to be part of something called “Special Editions Limited”—a subsidiary of Playboy Magazine. Hugh Hefner’s daughter, Christie started SEL in an effort to legitimize Playboy’s business affairs. Chuck soon found his work showing at art shows across the US, alongside the likes of Haring and Warhol.

“It was crazy,” he said, almost giggling to himself and I could only imagine what the experience of working for Playboy in the 90s must have been like. Either way, Chuck has had years—decades—to form his artistic vision—which really just comes down to the simple fact that making stuff equals survival.

“I keep making stuff because I have to. Self worth is based upon it—it’s your well-being—to give yourself validity for being on the planet you have to make something.” At the time he said this I knew little of The Dry Points, but it all falls into place—the vision, the spirit, the “you gotta go for it or you’ll regret it” attitude.

I needed to know more. But to fully tell Chuck’s story I wanted to get a look at his studio so we traded information and looked at some dates.

“Hey, I’m having some friends over on Sunday to watch the Packers game, you should come over and join us,” Chuck said. “There are going to be people way more interesting than me there. You should write about them, too.”

“Alright, see you Sunday at 11.”

It didn’t end well for the Packers that day, and while some fans were likely drowning their sorrows in a bowl of nachos, we had brushed it off and were talking art. I took in the game sitting next to Tom Crawford, longtime station manager of WMSE—a staple of the Milwaukee music scene for decades. Ironically, we talked about bird watching, a surprising passion of his.

Back in Chuck’s studio a few moments later I was talking to Brett. “The Dry Points did one show at City Hall, and a few thousand people showed up,” Brett told me, who during the game confirmed that this is a good time to be an artist in Milwaukee. There are a lot of people doing great work right now. As for The Dry Points work, they received a few offers for a couple of the pieces but want to keep the collection together.

“They’re like the wall art version of Robert Indiana’s Mecca floor. It needs to stay together.”

Brett neatly tucked the work back inside the large, thin wooden folder, and for the guys in the room it was like taking a trip back through time. “We’re in talks for giving this work a home as a collection,” Brett said, keeping things hush-hush for now.

The spirit of The Dry Points permeates every piece, and you can see that multiple personalities came together to create it—but magically it works together in a serendipitous and miraculous way. I couldn’t believe what I saw. It was clearly the remarkable vision of remarkable people.

I had to get home after a day full of a weirdly strange mix of sports and creativity and art. I hadn’t had a drink, but was drunk on it. I got home, and doing a little more research on the Dry Points web site found this paragraph embedded in their process:

We don’t believe in mistakes in the mark-making process. Each mark, however divergent, is a spark for the next band member’s move. At times it’s a sensical continuation, while at others, it spins the print into a completely opposite direction. If an impasse is reached by an individual, the print will be passed to another member, be reviewed by the whole band for next moves, or set aside for a later date.

The Dry Points methodology in that moment for me transcended simply a process to make art. It felt to me like a way to live your life, trial and error, get some help when you need it, and if whatever you are doing isn’t working put it aside and move forward.

Perfect.

- You can keep up with The Dry Points on their website.

- Also check out Tainted Loft on instagram.

- Photos by Nicholas Pipitone.